Reluctant Readers

“Even Though You Love Books, I Don’t”

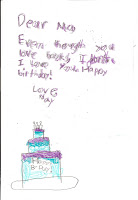

Today is my birthday. At 8:00 this morning, my eight year old son ambled down the stairs and handed me this homemade card.

Sweet, right? When I opened it up, this is what I saw:

For those of you having difficulty seeing beyond the purple highlights, let me make sure you know what it says:

Dear Ma,

Even though you love books, I don’t. I love you. Happy birthday!

Love,

Nay

I laughed out loud when I saw these words because while I get his point—he loves me more than he loves books—it also kind of sounds like my son is saying he doesn’t love books (which, as I established last week, is fine so long as he loves what books do for him).

All kidding aside, kids who don’t love books are not a unique breed. These are our reluctant readers and they pose a particular threat to literacy because as Mark Twain says, “The man (woman, child) who does not read, has no advantage over the one who cannot read.”

If you work with reluctant readers, here a few quick tips to help them over the hump and help them fall in love with what books can do for them:

- Don’t expect them to read things that are too hard.

- Let them choose what THEY want to read!

- Talk to them about books—let them know what’s out there to read.

- Get them interested in a series or popular author.

- Read aloud and remind them of the pleasure of stories!

On that note, I’m going to going to get Jon Scieszka’s Knuckleheads from my bedside night table and do some reading triage with Nathan just to make sure that I interpreted his words correctly and he wasn’t really saying, “I don’t like books…”

The Secret Society for Selecting Stories

Reluctant Reader 911

Does it always seem like it’s your students that like to read least that have the most excuses for not reading?

- I don’t have a book.

- I can’t find my book.

- I don’t like my book.

- I have to go to the bathroom.

Anything, but “I can’t wait to read.”

The hard reality of the situation is reluctant readers are the ones who need to read the most because very often they are reluctant because they are struggling. But we ask, “How? How do I get them to read more?”

What we’ve got here is reluctant reader 911 and what this calls for is:

- Be sure that somewhere in your room you have a bin of books designated for each of your reluctant readers. Instead of allowing these readers to return to your bookshelves on a daily basis, allow them one day to gather several titles that they think they might be interested in. Guide their choices and encourage them to put in picture books, comic books, non-fiction books and magazines. Be sure these collections contain no less than ten different titles. Forcing students who make a sport out of avoiding reading to take time to thoughtfully consider their interests helps to eliminate the “book” problems often faced by reluctant readers.

- Build in breaks. Nothing is more daunting to a child who knows that they are going to have to spend the next thirty minutes doing the very thing that they hate most. If you want to build stamina and commitment to reading, allow your reluctant readers to use a sand timer to help them measure reasonable chunks of reading time. When the timer runs out, allow them to get up and take a quick walk to the water fountain or stand up and stretch and then return to their reading. Even dedicated and sophisticated readers glance up from the page from time to time. Built in breaks makes the marathon seem do-able. And remember, for a reluctant reader, reading is a marathon.

- Validate their feelings. As teachers, we are very often cheerleaders for reading. We say things like, “What do you mean you don’t want to read? Reading is great!” And granted, we genuinely believe this, however, for the child who is reluctant, it’s merely a reminder of yet one more failing. Instead of coaxing, simply say, “Yep, I know how hard it is to do something you don’t want to do. When I don’t want to do something, I figure out a plan to make it do-able. Let’s figure out together what might work for you.”

Come Away from the Dark Side

On Friday, I met Andrew, a smallish, third grade boy who wore his distaste for reading like a badge of honor. We all know these kids. They proudly announce how they don’t read books and how reading is stupid and boring. Often, when these readers (or non-readers, as the case may be) make this proclamation, we teachers say things like, “Oh, Andrew, how could you say that? Stories are filled with action and excitement. Stories are wonderful.”

When we say things like that, our intentions are good. We know that if our students hate reading, they won’t want to do it, and if they don’t want to do it, they won’t practice and get better. It’s only natural to want to cajole them away from the dark and twisty side.

But I didn’t say that to Andrew when he told me that he doesn’t like to read. Instead, I said, “I get what you mean. Sometimes, when I read, I can’t picture it and I feel like it doesn’t really make any sense. When this happens, I don’t really like to read either.” When Andrew heard this, he softened a bit. He allowed me to come with him into his book and we flipped through the pages and talked about the pictures and how the pictures make the story come alive.

…Or I should say, I talked about that.

Andrew listened and then after careful thought and consideration, he said, “Yeah, but I don’t get how you do that. How do you see pictures in your mind?”

This took me by surprise. On the one hand, I recognized that Andrew hates reading because it doesn’t make sense, but on the other hand, I made the assumption he visualized as he read.

Our notions of what children can and should be able to do cause us to take for granted what students ARE doing. These assumptions can lead our teaching astray. Andrew’s comment was the quick jolt of reality that I needed to shake me awake and remind me to listen actively and adjust my teaching to his needs. Coaxing him from the dark side won’t happen from simply validating his feelings about reading. Now it’s time to give him the tools he needs to understand.

Reconsidering the Importance of Publishing

In Writing Workshop, I have long downplayed the importance of publishing. My work with children has always emphasized what writers do to get words down on paper, how writers change their words and grow their ideas. I’ve always felt that people who write for a living don’t publish everything, so why should we have the expectation that our young writers publish absolutely everything?

These days, I find myself rethinking the importance of publishing. At the New York State Reading Association conference that I attended this past weekend, I saw Kay Gormley and Peter McDermott from the Sage Colleges present on using technology in the classroom. I watched as they demonstrated how children could publish their writing on websites like StoryJumper and Blabberize. As I watched, I couldn’t help but wonder how these programs would motivate reluctant writers to want to write more. And then, I realized. Digital savvy, polished end products wouldn’t motivate only reluctant writers, they would make ALL children want to write to the finish. Not only that, it might make them value the whole process differently. I know I write differently when I know people will see my end product.

Kay and Peter definitely left me thinking hard about the importance of integrating digital technology into our literacy frameworks. The possibilities are endless and will surely better prepare children for our fast-paced, technology-driven world.

The Turtle and the Hare

In a blog titled Book Emergencies, I introduced you to my now fourth grade son Matthew, my feast or famine reader. On some occasions, he devours books, on others, he nibbles his way through them. Last month, Jeff Kinney’s Dog Days came out and when he got his hands on it, he read it in one day, staying up late to finish it. Since then, he has merrily returned to Lego magazine and his fifth reread of Club Penguin pick your own ending. In a conversation with other teachers, I affectionately referred to Matthew as “my turtle,” the one content to plod along slowly, slowly, slowly.

My other son, Nathan, is “my hare.” He’s a first grader who wants to read everything. He’s dying to read “chapter books.” In fact, very often he will pick up a Magic Tree House book and read several lines and not make a mistake.

Hallelujah, right?

Wrong. I am worried about Nathan, too. Sure, he can say all the words in Magic Tree House but he works awfully hard at it. All of his energy is poured into decoding and by the time he reaches the end of a paragraph, do you know what he has left for understanding? Zilch.

Matthew, on the other hand, understands everything. Recently, he read Amber Brown is Not a Crayon, another book below his “level.” Yet, as he read this story, he talked about how Amber is “forgetful” (like him, he added) and Justin is feeling “awkward” about moving. When he finished he told me that this book is “a lot like that saying ‘If you love something, set if free.’”

When he told me this, I nearly fell off my chair…and as I hit my head, a thought occurred to me. So, he reads all this easy stuff, but he gets it. In fact, not only does he get it, he goes deep.

Hmmm. Maybe Aesop was onto something when he told us about the turtle and the hare. Maybe slow and steady really is the way to win the race.

You Can’t Hurry Book Choice

Today I worked closely with a reader who was trying to choose a book. When I approached him, I sensed that he was somewhat reluctant. He struck me as the kind of child who would spend his entire reading time choosing a book if it meant he could avoid actually reading. My instinct was to take the “Hurry up, get a book, get back to your seat, and get busy reading approach.”

Then it occurred to me.

Reluctant readers very often don’t know what to choose because they don’t know what’s out there. Sure, I could rush Billy, but to what end? What will I have taught him about book choice? About stamina? About good readership?

So, I decided to invest the time to carefully guide Billy’s book choice. We scoured the classroom library together. As we thumbed through books, I told him about titles and authors that we encountered, eliminating things that weren’t of interest as we went along. Before long, we had narrowed his choices down to a small stack of possibilities.

As it turned out, Billy did avoid the entire reading period making his book selection. However, he now has a book he is excited about reading. In fact, he chose two books that he is excited about reading. Had I hurried him, he might have chosen something to placate me and I’d be happy for now, but he wouldn’t. And he’d be back in the classroom library tomorrow.