I looked at him and was awed both by his sensitivity and keen observation. As I digested this comment, I realized that books and reading have become Matthew’s dress rehearsal for life and because he reads, he understands his own life better. As a reading teacher mom, I love that this has happened, but what’s more, Matthew loves it and I think that’s what Peter Johnston was getting at. Matthew sees value in reading and THAT will keep him coming back to books for his entire life.

Losing the Stanley Cup: A Lesson for Teachers

A Smoothie at the Zoo

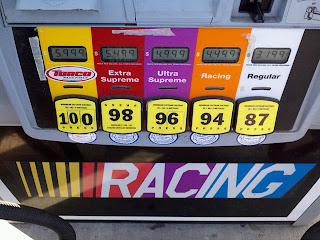

A High Octane Year

The Secret Society for Selecting Stories

An Evolution of Change in our Reading Diet

Literacy Gospel Unhinged

As a literacy coach, I travel from school to school. I don’t have a home base and therefore, often work in classrooms that don’t look even a smidge like what my own classroom used to look like. Sometimes desks are organized in rows and it’s difficult to move about the room. Sometimes there’s no meeting area. Sometimes there’s no easel or markers or paper. Sometimes the classroom library is nothing more than books crammed onto a shelf in the back corner of the room. I work within the parameters I am given and have to think on my feet about how to adjust to mediate my vision for good literacy instruction.

One day, while visiting a second grade classroom, I gathered the students on the carpet and taught a mini lesson. At the end of the lesson, I released the students to read independently. Generally speaking, it is my practice to invite children to find their comfy nook around the room and cozy up with their book, but in this classroom, the desks were butted up against one another in three long rows. It wasn’t clear to me where the students would comfortably and safely go, so on this day, I simply instructed the students to return to their seats and do their independent reading there. It all seemed relatively straightforward until a couple of weeks later when I was having a casual conversation with one of the teachers who observed this lesson. She and I rapped about some of the things she was doing differently and she shared that she had stopped having her students read around the room and had them now reading at their desks. I was surprised when she told me this so I asked her why. “Well, Kim, when I watched you, that’s what you did.”

This particular teacher had nurtured her classroom environment all year and had made sweeping changes. She had a well-stocked, well-organized classroom library and her students had book baggies that they were reading from religiously every day. It surprised me that she did not question me before shifting to a practice that seemed so counterintuitive to the work she had been doing. But I was her expert. She saw me do something and therefore, it was so.

At first, this shocked me but as I thought about it, it occurred to me that I do the same thing. I once heard Dick Allington discuss the “five pillars” of reading instruction: phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. When he said this, I took frantic, thorough, copious notes. I memorized them so that I could recite them backwards and forward. And I have repeated his words on countless occasions—in spite of the fact that I had the hardest time explaining the difference between phonics and phonemic awareness instruction in the classroom. Aren’t they kind of one in the same when you’re teaching? I wondered. Dick Allington is one of my experts. He said it, therefore, it was so. I didn’t trust that I would be worthy of questioning the gospel spoken by one held in such high esteem.

When it comes to great literacy instruction, it isn’t enough that Lucy or Dick or Irene said it. Inquiry and reflection help us hone our skill and practice as educators. If we are going to make lasting changes, we cannot heed everything we read and see and hear as the literacy gospel. Change is rooted in understanding and the path to understanding is paved with questions. When you’re confused or uncertain, stop at nothing to find answers to the things that do not make sense.

Boy Friendly Classrooms

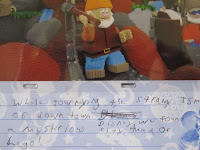

My family and I recently returned from a memory-filled vacation at Disney. While there, my fifth grade son Matthew had the foresight to think about how he would preserve these memories and asked if I would purchase a photo album so that he could make a scrapbook commemorating the highlights of our trip. Both touched and thrilled at this suggestion, I overpaid for a Mickey themed album, brought it home, developed our photos, and Matthew went to work. I sat beside him as he busied himself with sliding the pictures into the plastic sleeves and wrote catchy captions to describe the events of our vacation. I watched intently as he worked. He misspelled words and scribbled them out and rewrote them. His handwriting was messy. There was none of the meticulousness that I remembered applying to similar projects in my childhood.

As he worked, I thought a lot about what I had read that morning. In Pam Allyn’s Best Books for Boys: How to Engage Boys in Reading in Ways That Will Change Their Lives (amazon affiliate link), she quoted Harvard psychologist William Pollack who says, “More boys than girls are in special education classes. More boys than girls are prescribed mood-managing drugs. This suggests that today’s schools are built for girls, and boys are becoming misfits.” And it was these words that forced me to muster every ounce of self control in me and refrain from chastising his work. I wanted to say, “Can’t you do that a little neater? Don’t you think it would be better if you were more thoughtful?” But I didn’t because I realized that what I wanted was to cloud his vision with what I perceived to be a more correct vision. I wanted him to do it my way. My female way.

This got me thinking about how often we do this in schools. Are children, particularly boys, doing things “wrong” as often as we think they are? When they write, is it really not that good or is it that it doesn’t match a preconceived notion of what they should have written? Are they really misbehaving or is it that they are not behaving in the way that we would have? Is their artwork messy because they didn’t color in the lines or is it that they intended to add action in ways that we could not conceive of?

Most school faculties are comprised of a female majority. School activities and classroom management and expectations of how children comply are driven by the female psyche. Could it really be that the female way of thinking is different enough from males that we create environments that alienate half of the learning population? On this one occasion I stopped short of committing the crime of imposing hearts and borders on my son’s scrapbook but I have to wonder, how many times did I not? I am willing to stand among the convicted when it comes to admitting guilt of making boys feel like misfits. But I am repenting. I am thinking hard about what I will do differently to embrace gender differences and create learning environments that cater to the unique needs of boy learners.

To start, I will no longer insist that children write or read sitting down. If they need to stand and shift from side to side, so be it. I will no longer insist that reading time be uninterrupted by bathroom breaks or short periods of gazing out the window. If they need to let their minds wander or to think more about what they are reading, so be it. But past this, I’m not sure what else I should change and that is why I am appealing to you, my readership, to share your suggestions for modifying common practices to make boys feel more at home in the classroom. What else can we do in schools to close the gender gap?